Information literacy in the digital archive: Empowering students to think critically and interrogate information

Felix Barnes, Publishing Manager, AM and Courtney Priday, Senior Editor, AM

AM specialises in digitised primary sources and the technology that brings them to life for education and research. With AM you can search content from hundreds of published thematic databases, or manage, publish and share digital assets from your special collections to unlock their full research value.

In an age of misinformation and distortion, primary sources are more vital than ever. They are an essential tool for understanding our contemporary world and critically evaluating how the past transforms the present. In a 2013 lecture the historical novelist Hilary Mantel characterised the essential process of history as “loss, then retrieval”.[1] First, historic sources must be retrieved and made accessible but the most crucial step of this retrieval in order to make history, is for them to be understood. This can only be done through information literacy, which is why supporting the development of these skills is central to the work we do at AM.

Through our collections we encourage users to think critically about primary sources and develop these skills so they can be applied to make balanced judgements about information found anywhere.

It’s rare that a single primary source – a document from an archive, say – can be understood or used in isolation. It exists within a rich, complicated and often compromised context that needs to be examined. A reader needs to understand what can be learned from the source and what can’t through this context. This context could include things such as the way the archive was assembled, why it was assembled, why it survived, what wasn’t retained or what was lost; as well as the history and historiography within which the source may sit. The answers are not always easy to find but the questions are key to building the information literacy that enables users to think critically about these sources and use them appropriately in their research.

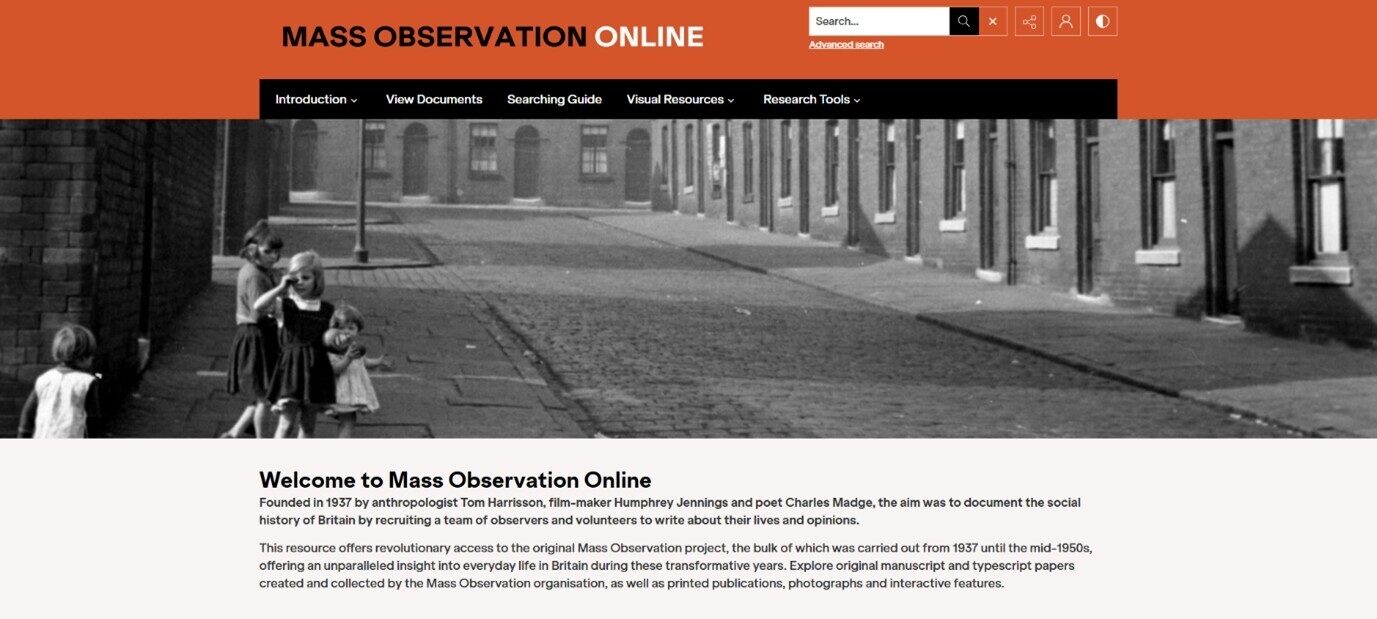

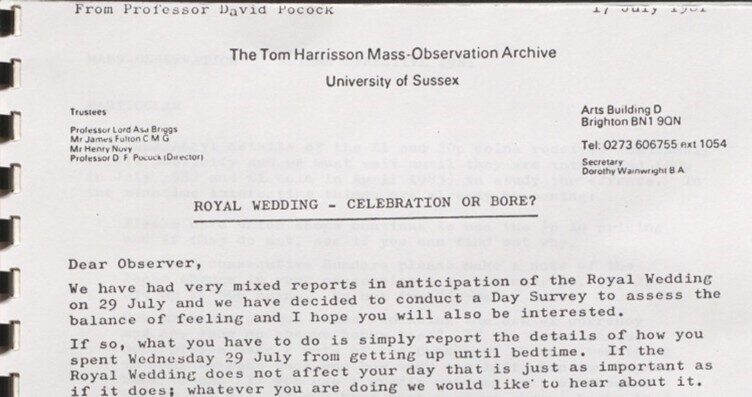

Take for example Mass Observation Online, published by AM. Mass Observation, and its successor the Mass Observation Project, were schemes in Britain that aimed to capture the views of the British public by asking them to keep diaries and answer questionnaires about a range of topics. The Mass Observation Online archive of their responses is undoubtedly an incredibly rich resource for understanding elements of twentieth and twenty-first century Britain – but content published alongside the archive reveals its limitations.

An essay by Stephen Brooke, University of York, highlights the demographic skew of the 'Observers’ responding to Mass Observation.[2] It encourages users to interrogate what information is missing from these sources and how this impacts the use of information that is available.

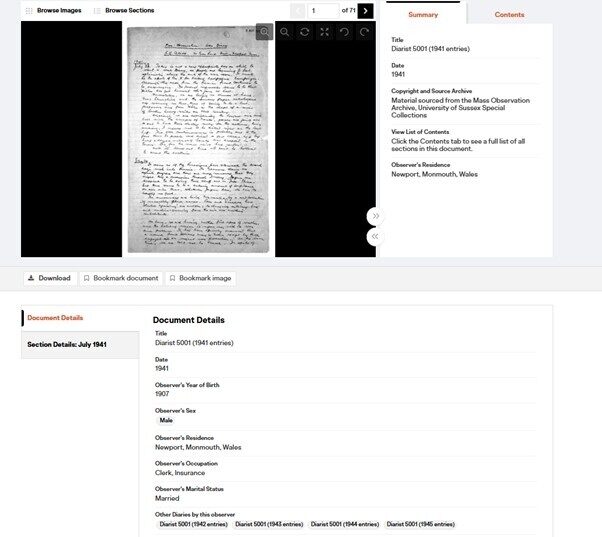

To support users' archival literacy, metadata is also provided alongside sources, drawn from archival catalogues and created by an editorial team. This provides the scaffolding to information within the source of how it has been categorised and indicates the information that has been deemed the most valuable in this process. For example, in Mass Observation Online, metadata includes Observer’s Sex, Year of Birth, Residence and Occupation suggesting to the user that these categories of information have been verified in the source and are important to the study of these sources, before they have even read the document. This additional layer of information can (and should) in turn also be interrogated using the skills exemplified in contextual essays to create rich understandings of the source material and their histories.

AM collections, such as Mass Observation Online, are designed to provide users not only with access to information in the primary sources digitised but to also support their development of the key critical thinking skills needed to uncover their meanings. This skill development empowers our users to develop informed views of the past to engage fully with the society of the future.

References

[1] Mantel, Hilary, “Royal Bodies”, London Review of Books, Vol. 35 No. 4 · 21 February 2013

[2] Brooke, Stephen ‘A history of the Mass Observation Project’ Mass Observation Project (Marlborough: AM, 2020)

Recent posts

The blog highlights American Committee on Africa, module II's rich documentation of anti-apartheid activism, focusing on the National Peace Accord, global solidarity, and student-led divestment campaigns. It explores the pivotal role of universities, protests, and public education in pressuring institutions to divest from apartheid, shaping global attitudes toward social justice and reform.

This blog examines how primary sources can be used to trace the impact of young voices on society, particularly during pivotal voting reforms in the UK and the US. Explore materials that reveal insights into youth activism, intergenerational gaps, and societal perceptions, highlighting their interdisciplinary value for studying youth culture, activism, and girlhood across history.