World's Fairs: An International Obsession

As my interest in World’s Fairs creeps ever closer to obsession, my expectations were sky high when, last month, I was lucky enough to attend EXPO 2015 in Milan, the current incarnation of the centuries-old tradition of World’s Fairs. In light of our forth-coming resource, World’s Fairs: A Global History of Expositions, I was fascinated to see how modern expos compared to the Crystal Palace exhibition of 1851, or the futuristic fair of New York in 1964, and experience something comparable to these phenomenally influential historical events.

Crowds on the central walkway

The initial plans that had been released did nothing to manage my expectations, forecasting a city of waterways that would join up Milan’s canal network and allow visitors to punt to the various attractions. In keeping with the fair theme of sustainable food, a local produce garden would be mandatory for every participating country and the fair site would be a lush ‘urban farm’ reflecting the agricultural heritage of the location.

But budgets and time constraints got the better of the organisers, and now the site rests on a concrete slab of over 1,000,000 square metres. There were some lacklustre planters dotted around with herbs suffering in the summer heat, and as well as lacking gardens, most countries chose to ignore the theme entirely, opting for exhibits that simply promoted their country as a tourist destination.

The Israeli pavilion and inside the UK pavilion

The intention behind the fairs hasn’t changed much since their 19th-century-origins, presenting a “global showcase” for the best technology with opportunities to display wealth and promote a national ‘brand’. The implementation, however, has evolved significantly. Gone were the vast halls of raw materials, machinery and artworks recorded at historic fairs, and instead the 2015 pavilions included interactive displays, touch-screens and immersive light and music shows, while others relied on evocative films and decoration.

The Monaco pavilion and the Kazakhstan pavilion lit up at night

The innovation and national produce that were missing from the exhibits were, however, realised in the design and execution of the architecture. The Japanese pavilion, for example, is made from Japanese Larch supported by carved joints in a construction technique replicated from ancient Japanese temples, the Brazilian pavilion is accessed by an entertaining climbing net while the walls of the Israeli pavilion are planted like fields designed as ‘vertical farms’. The spectacle of the fair was much more without than within the buildings, and the commodity that the countries aimed to showcase typically an idea or a feeling rather than a tangible export.

Since the Osaka fair of 1970, China and Japan have arguably lead the expo movement, hosting international events as well as countless national versions. And while northern European nations are still active participants, the future of expos is coveted by the Middle East, with Kazakhstan hosting the interim horticultural expo in 2017 and Dubai the next World’s Fair in 2020. Some are wary of increasing capitalist hubris, the omission of the good – if often unrealised – intentions of previous fairs, and the potential human cost (as reported from other large international events) that this focus on oil-rich developing nations may encourage. Others see the expansion of the fair movement as an opportunity to promote international values. Fairs have never been and look unlikely to ever be without controversy, or the fascinating, or the downright bizarre. And I’m more obsessed than ever.

World’s Fairs: A Global History of Expositions – which digitises primary source documents from fairs in the early 19th-century right up to Milan 2015 – will be published in spring 2016.

Recent posts

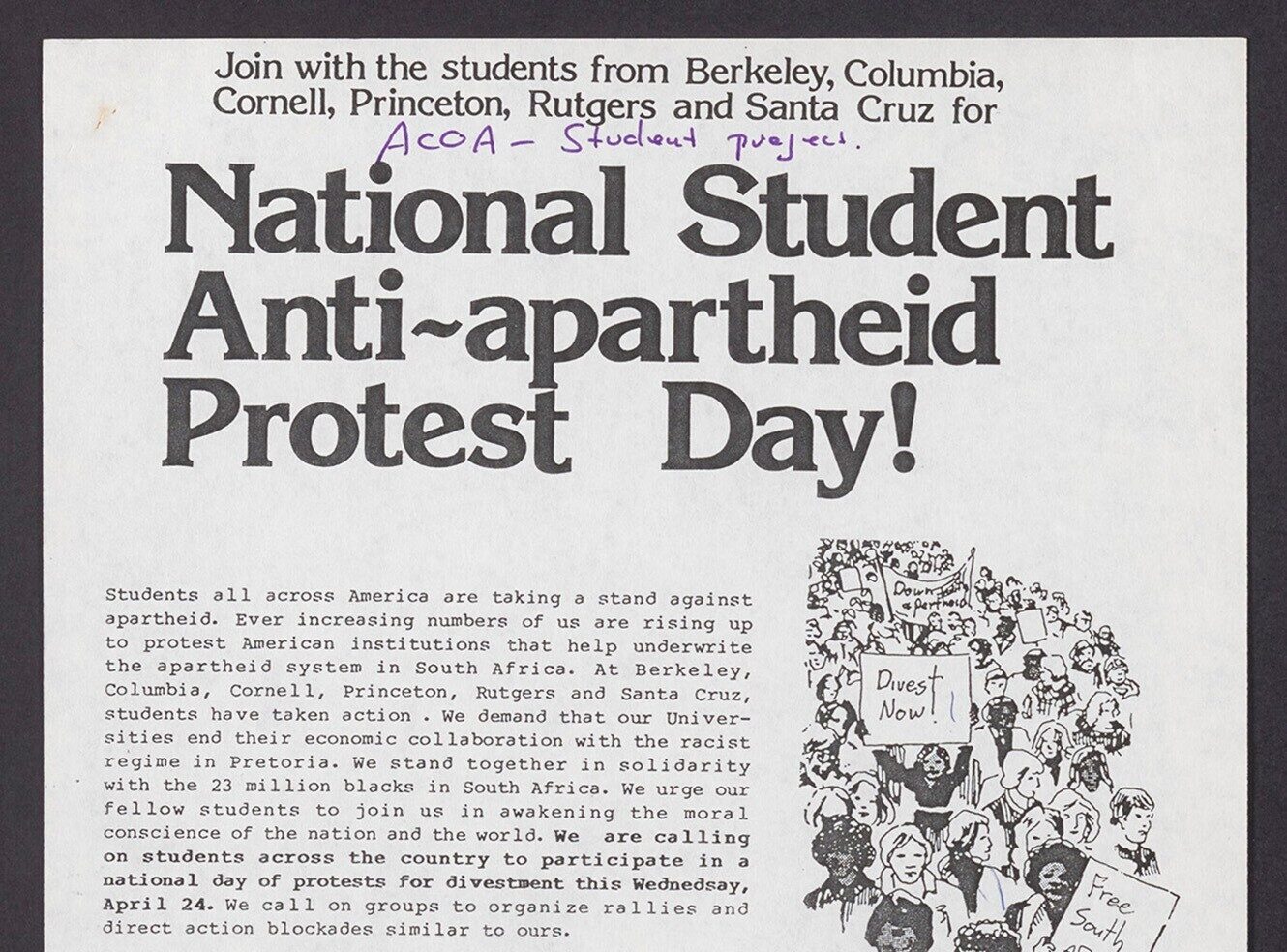

The blog highlights American Committee on Africa, module II's rich documentation of anti-apartheid activism, focusing on the National Peace Accord, global solidarity, and student-led divestment campaigns. It explores the pivotal role of universities, protests, and public education in pressuring institutions to divest from apartheid, shaping global attitudes toward social justice and reform.

This blog examines how primary sources can be used to trace the impact of young voices on society, particularly during pivotal voting reforms in the UK and the US. Explore materials that reveal insights into youth activism, intergenerational gaps, and societal perceptions, highlighting their interdisciplinary value for studying youth culture, activism, and girlhood across history.