Defending the Enemy: John Adams and the Boston Massacre of 1770

On the evening of 5th March 1770, in a snowy Boston, eight British soldiers led by Captain Thomas Preston confronted a crowd of Bostonians, who had gathered to protest outside the Custom House. Ignoring Preston’s command to disperse, the angry mob closed around, throwing snowballs and oyster shells at them.

When one of the missiles struck Private Montgomery, he discharged his musket after yelling to his compatriots, ‘Damn you, fire!’ Accounts vary as to what happened next but they all end with the troop firing into the crowd. As the smoke cleared three people lay dead and several others wounded, two of whom later died of their injuries.

Paul Revere’s engraving of the Boston Massacre, copied from an earlier engraving by Henry Pelham (March 1770). © Public Domain.

Colonial America contains numerous documents that provide fascinating insights into the aftermath of the Boston Massacre, including the proceedings of the subsequent trial of the soldiers and their defence by an unlikely advocate.

In wake of the events of 5th March, the colonists’ outrage compelled the government to arrest Preston and his men on the charge of murder, accusing the soldiers of ‘being moved and seduced by the instigation of the devil and their own wicked hearts’.

In the months before their trial, a media battle was waged between loyalists and patriots as to who was to blame for the incident. Paul Revere’s famous engraving of the event for example characterised the soldiers as ‘Like fierce barbarians grinning o’er their Prey’ and depicted them lined up in front of ‘Butchers Hall’.

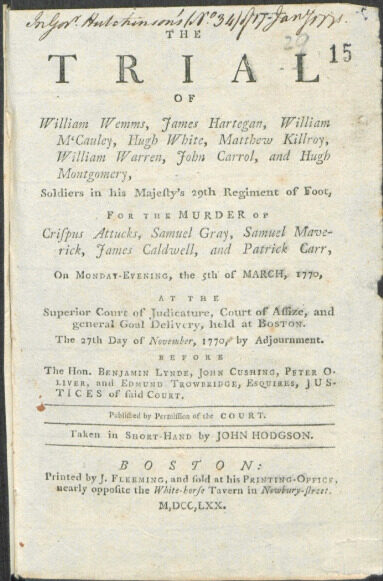

The trial of William Wemms, James Hartegan, William McCauley, Hugh White, Matthew Killroy, William Warren, John Carrol, and Hugh Montgomery, 27 Nov 1770. Image © The National Archives London, UK. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Such was the animosity levelled at the soldiers no lawyer dared to come forward to defend them. Ultimately however aid came from a surprising quarter in the unlikely figure of John Adams, a patriot and one of Boston’s most respected attorneys (and a future President of the United States). Adams had no sympathy for the British government and was a strong opponent of the Stamp Act and any form of taxation without representation. Yet he believed that the accused were innocent of the charge of murder and deserved a fair trial.

Adams firstly secured the acquittal of Captain Preston on the grounds that the men under his command had fired without orders. In the following trial of Preston’s men in November 1770, Adams pleaded that the soldiers had acted in self-defence and asked the jury to consider themselves in the shoes of the soldiers and whether any reasonable man would not have concluded that they were in danger of their lives when surrounded by a hostile crowd chanting, ‘Kill them!, Kill them!’ The arguments of Adams led to six of the soldiers being found not guilty whilst Montgomery and one other received the lesser verdict of manslaughter.

Although vilified at the time, Adams later reflected that his defence of the British soldiers had been ‘one of the best pieces of service I ever rendered my Country’, having upheld the principles of justice and the right to a fair trial regardless of any predilection. As Adam said in his closing statement at the trial:

Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.

For more information on Colonial America, including free trial access and price enquiries, please email us at info@amdigital.co.uk

Recent posts

The blog highlights American Committee on Africa, module II's rich documentation of anti-apartheid activism, focusing on the National Peace Accord, global solidarity, and student-led divestment campaigns. It explores the pivotal role of universities, protests, and public education in pressuring institutions to divest from apartheid, shaping global attitudes toward social justice and reform.

This blog examines how primary sources can be used to trace the impact of young voices on society, particularly during pivotal voting reforms in the UK and the US. Explore materials that reveal insights into youth activism, intergenerational gaps, and societal perceptions, highlighting their interdisciplinary value for studying youth culture, activism, and girlhood across history.